The title of this has very little relevance, it's more because I wanted to make a reference to Oasis. There have been so many reports proving the benefits of inactivity that it would be a waste of yours and my time to elaborate on it.

To give some brief context, I’m writing this primarily as a way to give myself confirmation bias, which sounds pretty funny, but sometimes it's needed. I’m faced with a dilemma most people face in their investing journey; however, I feel as if my current situation is a bit different due to my age. While I’ve never explicitly stated my age, I have alluded to it at times, and for those wondering I turned 17 a couple weeks ago. Being 17 presents a few interesting challenges around risk appetite, portfolio concentration and time horizons. My portfolio is insignificant relative to my future earnings power, but large enough that consistent above average returns will earn me a killing over a few decades. My time I can allocate to investing will most definitely decline in the next 2 years as I start University, so how do I set my portfolio up for that now? Plus how do I deal with my own psychological shortcomings with investing?

Portfolio Concentration and Earnings Power

Thus far I’ve heard two arguments as to how a portfolio should be structured relative to earnings power. The first is to have extreme levels of concentration at a young age because even if one position blows up, “you can afford it.” The second is to take advantage of the few extra years of compounding, and perhaps counterintuitively, play it safe and diversify. While I don’t know the answer nor does anyone really, it seems to be an interesting thought exercise.

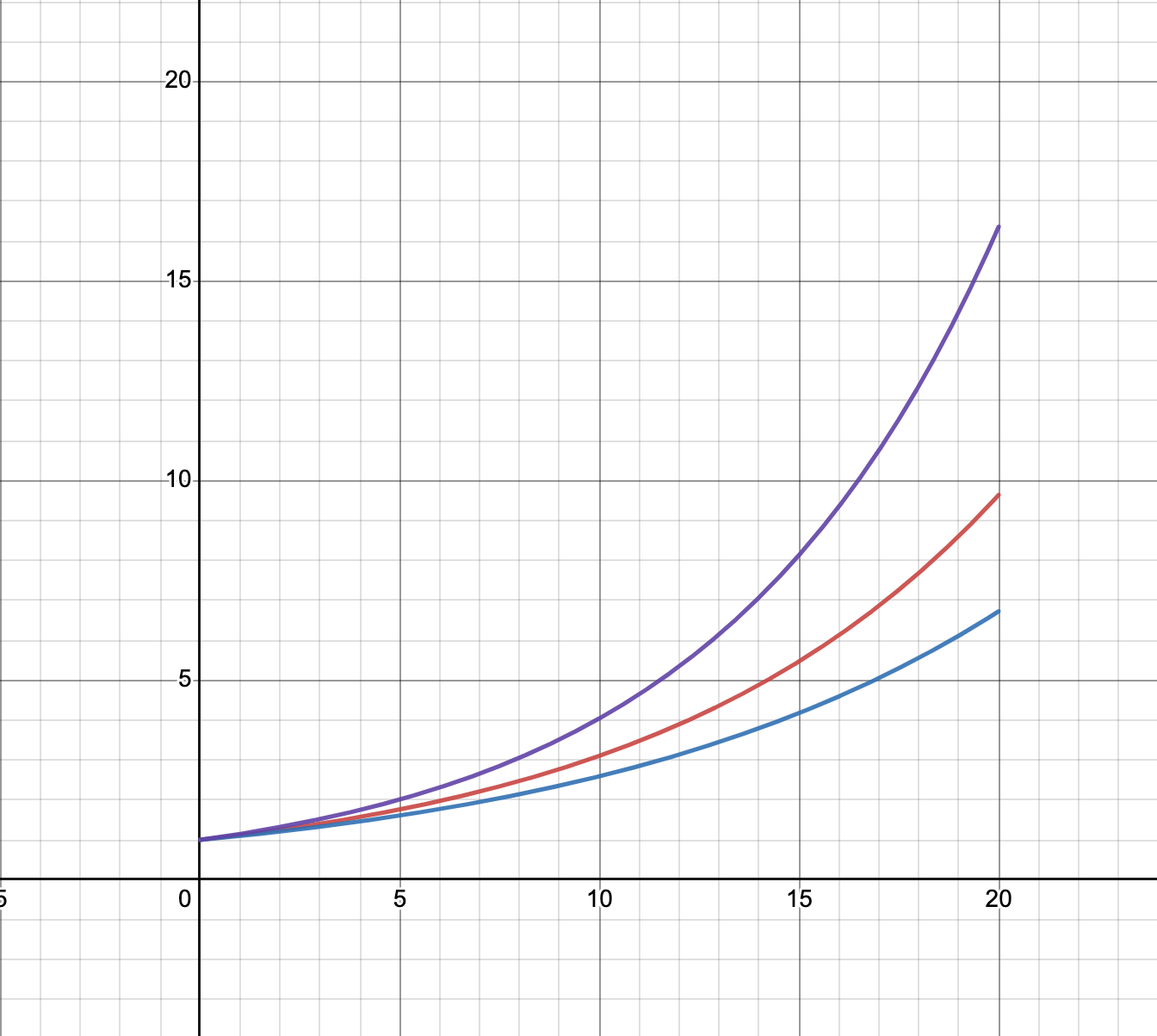

Assuming a 10% annual return for 20 years, this yields a 6.7x return. At that point I will be 37 and hopefully fitting quite comfortably in a high paying job somewhere. Taking the average salary for the field I want to work in and comparing it to the value of my portfolio after the 6.7x return makes my portfolio seem rather insignificant. Saving just 50% of my income for 3 years would yield the same results. It almost seems stupid to preserve capital in an attempt to take advantage of the few extra years of compounding. Granted 10% annual is somewhat mediocre, so what about 12 or 15%? I made a quick Desmos graph to see.

Even with a 15% annualized return for 20 years, I would return ~16x. Again comparing that to 50% of the average salary for my desired job, it would take just 8 years to generate the same amount of money. In some ways it's pretty disheartening. Granted I am excluding the fact that I may be able to add to the portfolio over that time, but I’d rather bet that I won’t be able to with all the time I will be spending studying.

Based on that, it seems pretty unreasonable to go for anything less than 20% annual at my age. Thus also suggesting that I need to swing rather large when those opportunities present themselves. While that may not be for everyone, I think it's important to keep in mind that for someone like me, losing my entire portfolio now would be insignificant in 20 years. Of course going for 20% returns requires its own set of skills that I’ll need to refine a bit.

Uncertainty

Despite playing chess games that lasted over 4 hours for several years, I struggle with patience in regards to investing. I think it's because it requires a different set of patients. For my purposes I will define patients as the ability to tolerate uncertainty. Therefore there are two types of patience: toleration of controllable uncertainty and toleration of uncontrollable uncertainty.

Controllable uncertainty is when, despite a non definitive outcome, you can affect the steps taken to reach it. Shaking the hand of your opponent before a chess game does not make the outcome of the game certain, but from then on the moves one chooses to make increases the certainty of the outcome. Opening with e4 has a higher likelihood of winning games than h4 and so forth. The outcome is completely dependent on how well you play and thus is controllable.

Uncontrollable uncertainty is an unknown outcome where there are no controls for you to influence the outcome. Time and uncertainty are proportional here. The more time that goes by, the more uncertainty there is. I consider this to be what investing is. Yes there are factors that can increase the likelihood of a favorable outcome; however, once a certain point is reached, nothing more can be done. Say for instance you invested in Amazon in 2004, you saw the unique culture, growth prospects, etc… Then what if Jeff Bezos died the next year or a fire occurred at their warehouse destroying all their merchandise? Well, your thesis is ruined.

All too often investors think they’re playing with controllable uncertainty when they’re really dealing with uncontrollable uncertainty. It's a bit like when your brother hands you the control, but never turns it on, so he can still play. You think you’re the one playing, so you get swept up in the feeling of success or the misery of failure, but at the end of the day you're not doing anything and no matter how proud you are, it wasn’t you that did any of it.

In Howard Marks’ memo The Illusion of Knowledge, he calls out the absurdity of forecasting by showing just how complex it would be to forecast the US economy. There are billions, if not trillions, of nodes between individuals and it would just be plain arrogant to assume you can forecast them all correctly. Then one must figure out the significance of each node and so on. He also quotes Morgan Housel’s newsletter where Mr. Housel outlines Cromwell’s Rule:

“Never say something cannot occur… If something has a one-in-a-billion chance of being true, and you interact with billions of things during your lifetime, you are nearly assured to experience some astounding surprises, and should always leave open the possibility of the unthinkable coming true.”

Investors, myself most definitely included, seem to struggle with giving themselves up to chance. They continue to play chess while they’re really just playing a game of dice. I believe this to be a main cause of portfolio churn. As a perfectionist myself, I find it incredibly difficult to accept that there isn’t really anything else I can do to improve my returns. It's very difficult to be patient and wait for an idea to play out when I see something that may yield a few basis points more. Then consequently, this actually yields lower returns.

While there are numerous companies out there that could crush anyones portfolios in terms of returns, it seems kinda absurd to think one can find that stock out of over 40,000 publicly listed companies. You need to get comfortable with your portfolio and almost adopt a defeatist mindset. Rather than spend hours and hours looking for a company that may return 1% more annually than a stock in your portfolio, why just not do anything at all and accept this is pretty close to the best you’ll be able to do. Spending all that extra time seems pretty futile. Time is even more valuable than money, so why not spend this time with family or friends? People idolize Warren Buffet, myself included, but many are not aware of the effects his job had on his wife and family.

Now with all this pessimism it's important to note that I’m not arguing to just give up or be satisfied with your portfolio, but rather once you hit the point of diminishing returns on your time, why bother with much else? Nor am I arguing for a coffee can approach either. If you stumble across a company that you believe will generate something like 15% annualized more than a current holding, by all means buy that one. For my own portfolio, once I suspect my portfolio can return 20% annually, for a stock to make it into the portfolio it must return at least 30% annually. Admittedly, I don’t have any evidence to back that up, it's more just a feelings thing.

What is the best portfolio structure?

Returning to the introduction for a moment where I mentioned that I’m writing this as a form of confirmation bias may give an idea of what structure I think is best. The best way to structure a portfolio is different for everyone. Let’s say you're trying to win a gold medal at the olympics. You see Phelps kill it and want to try swimming. After struggling for a few years you may realize it's not for you. Then onto gymnastics after seeing Simone Biles crushing it. Samething, struggle for a bit then quit. You take in what made Phelps and Biles so great like their work ethic or diet, but it's only after you look at your own attributes do you find what sport is best for you. Maybe you’ve got super long legs and great endurance, so you try running. Turns out that was the path for you and as you stand on the podium looking back at your success, you wonder why did I ever waste so much time trying sports I’m just not built for when I could’ve been running?

With this crude analogy I’m attempting to suggest that there are multiple ways to get wealthy and it doesn’t make sense to copy some other great investor if you don’t have the same attributes as them. Why try and copy Guy Spier if you know you won’t be able to sit on your hands for years at a time? I myself have jumped around into different portfolio structures trying to copy the most successful investors, but I just couldn’t sit on my hands for long enough. It’s caused me to interrupt a few years of compounding, and while I have learned a lot, it's a little annoying in hindsight.

It’s important to notice your own psychological shortcomings, so that you can build your portfolio in such a way that counteracts those very shortcomings. If you can’t handle volatility, why only hold a few stocks? No matter how great the plan is, if you can’t stick to it then what's the point? Bill Miller puts it well, as he usually does,

“time, not timing, is key to building wealth in the stock market.”

The 240/45 Portfolio

I thought up this structure as a way to both reduce churn, while also satisfying some of my perfectionist tendencies. With this system there will be 2 holdings with ~40% weightings each with the intention to hold for >10 years and then 4 holdings with 5% weightings. The 40% holdings require a large margin of safety combined with above average growth prospects. I won’t be mentioning the two that I have picked (not like it matters), but there are certain to be other opportunities with the wackiness of the markets over the last few years. Each is likely to deliver 25%+ returns annually and I can almost guarantee that they will be around in 20 years. The next 4 holdings are split into medium and short term ideas, so that it forces me to continue searching, while also giving me the satisfaction of implementing a thesis after all the work I’ve done. Hopefully also preventing me from messing with the two core holdings.

It seems kinda funny that, after writing about how we can’t forecast the future, my portfolio is going to become so concentrated, but it's important to note I was arguing that your odds can’t be improved beyond a certain point, not that they can’t be improved. I sure as hell wouldn’t want to hold something like Tesla compared to Mastercard, but Mastercard compared to Visa is much harder.

To further shut down my other tendencies, I will lock myself out of my brokerage account. To do so indefinitely would be pretty stupid because even though a coffee can portfolio has worked, I’m not sure of how many failed, i.e survivorship bias. Thus to unlock my account, I’ll be creating a checklist that must be done before opening the account. It will be filled with questions like:

Are the projected returns of the incumbent so significantly worse than the potential incoming company that luck is no longer a factor, and it would be stupid not to allocate cash to this new company?

Have I let my own excitement around this new idea die down before looking to start a position?

The general idea is that this will hopefully slow my process down and put more significance on each individual trade, thus reducing the quantity of trades. To further reinforce the barrier to trading, I’m giving my mom my account to make a new username and password, so that I must go through another person to make any trades. Eventually these training wheels will be taken off as I get more comfortable passing on ideas and increase the conviction in others, but for now this seems like a pretty nice approach for me. I’d encourage anyone to find their own wacky ways of combating their tendencies because not only is it a fun thought exercise, but also may boost your portfolio returns.

For your troubles, a one page thesis one Marvipol Development

Poland is the 6th worst performing market over the last three years with an impressive -28.6% return. To compound their problems, the Russo-Ukraine war has scared many investors from the region. This of course is an opportunity. Marvipol is a Polish residential and warehouse developer in Warsaw, Gdansk, and Wroclaw that looks almost priced for bankruptcy at 2x earnings. Of course there are some reasons for it, but it seems unlikely that they could justify pricing Marvipol at 2x earnings.

The Bank of Poland recently raised the minimum down payment on mortgages to 50% which has tightened the market quite substantially. The Russo-Ukraine war has also caused consumer sentiment to deteriorate. Energy prices have skyrocketed and many no longer want to live in a country neighboring Russia. Luckily, Marvipol is insulated from much of the impact. The 7 largest cities in the country are basically the only places in all of Poland with positive population growth. People are moving from rural areas, now called “umierlania” which means place to die, to the cities like Gdansk and Warsaw. Any fear that Russia may invade Poland is also extremely irrational. For one Poland is a NATO member and also Russia is already failing in Ukraine. It is only a matter of time before these concerns go away, and when they do, the Polish real estate market should return to normalcy.

In the meantime, Marvipol is hardly struggling. They have 1025 units under construction with 42% already presold, despite the challenging environment. In total there is 189 thousand square meters under construction or in the preparation phase. There is also some funky accounting going on with revenue declaration. Marvipol has over 400 million Zloty that has yet to be declared as revenue because the contracts have not been officially completed. It is possible that the buyer could back out of the deal, but even if half of them do, at 20% gross margin that's still 40 million of gross profit. In 2020 and 2021, Marvipol opportunistically invested 350 million zloty into land, which is 50% more than Marvipol’s current market cap. That should provide an incredibly safe floor for the company. They are hoping to sell 800 units per year, but with the current market environment they had to delay their plan a bit.

More recently, Marvipol has partnered with an Italian developer, Panattoni Group, to build warehouses in Poland. Poland is becoming more digitized with Allegro and now requiring more warehouse space, much like the US has needed the past few years. Marvipol’s hurdle rate is 18% return on equity for their projects and they can not take longer than 3 years to complete. They now have 261 thousand rentable square meters across the country to be sold with ~200 million zloty of investment, which has generated 27.8 million zloty of net income for the first 9 months of 2022. If the residential segment were to be worth zero, Marvipol would still be trading at <10x earnings.

They are also committed to returning cash to shareholders. In 2020 the dividend was 20% of operating profit and they will increase that by 1000 basis points each year eventually stopping at 50% of operating profit by the end of this year. If operating profit were to stay flat for this year, the dividend would be 20%. I would also suspect a rerating as the stock is trading at a valuation that is a third of their peer group. While I’m still not certain on forward returns, this certainly looks promising.