Thanks to Willis Capital on twitter for answering a few of my questions about Vulcan.

Intro

Speaking from personal experience, I think at one point in our childhood most of us had an obsession with construction vehicles. I can remember the Tonka Trucks I would push around the house and load them with sand on the beach or dirt and gravel from the playground. Then I thought I was really special when, for Christmas, I got one of those Hot Wheels cars you could drive. After however many years it's been, I'm back on the construction vehicle party train, but not with Tonka Trucks, this time with Vulcan Materials.

Vulcan Materials, the largest producer of crushed stone, gravel, sand, and even a major producer of concrete and asphalt, is in a pretty boring business with seemingly bad economics. Yes it may be boring, but boring is good and no, it has great economics. I’ll let Peter Lynch explain this one:

“I’d much rather own a local rock pit than own Twentieth Century- Fox, because a movie company competes with other movie companies, and the rock pit has a niche. …Certainly, owning a rock pit is safer than owning a jewelry business. If you’re in the jewelry business, you’re competing with other jewelers from across town, across the state, and even abroad, since vacationers can buy jewelry anywhere and bring it home. But if you’ve got the only gravel pit in Brooklyn, you’ve got a virtual monopoly, plus the added protection of the unpopularity of rock pits. The insiders call this the “aggregate” business, but even the exalted name doesn’t alter the fact that rocks, sand, and gravel are as close to inherently worthless as you can get. That’s the paradox: mixed together, the stuff probably sells for $3 a ton…What makes a rock pit valuable is that nobody else can compete with it? The nearest rival owner from two towns over isn’t going to haul his rocks into your territory because the trucking bills would eat up all his profit. No matter how good the rocks are in Chicago, no Chicago rock-pit owner can ever invade your territory in Brooklyn or Detroit.” - Peter LynchIf someone like Peter Lynch speaks so highly about something, its definitely worth looking into, so thats something I’ll be doing.

History

Although the company name “Vulcan” wasn’t given until 1956, the company, formally known as Birmingham Slag, (what a charming name) was started back in 1909 by Henry Badham and Solon Jacobs. They recognized that slag, a byproduct from the smelting or refining of metals, could be used in road construction. seven years later, Charles L. Ireland (wonder where his ancestors are from) purchased Birmingham Slag who then gave the company to his kids to run. During the 20s, Birmingham Slag benefited from the good roads movement of the Progressive era. As the name suggests, people wanted good roads. Birmingham slag actually remained profitable every year until 1932, and after the Great Depression they actually began growing even faster. Partnering with the Lambert Brothers in 1944 to expand their company, Birmingham slag provided some immense growth due to the added scale, but that was just the beginning. In the same sense that U-Haul was able to benefit from the interstate highway system, Vulcan was as well, in a much more obvious way. The passing of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, granted $25 billion ($275 billion inflation adjusted) for the construction of 41,000 miles of highway across the country. In the same year, Bernard A. Monaghan merged Birmingham Slag with Vulcan Detinning Company of Sewaren, New Jersey to go public and raise money for growth. Thus the name Vulcan Materials Company was born. (There's a misconception that the name Vulcan comes from the city of Birmingham's symbol, Vulcan, god of fire and the forge) Following the busy year of 1956, management wanted more, going public on January 2, 1957, while also merging with nine separate companies at the same time. From this a chemical division was set up. Pretty much from 1957 until 2005, Vulcan acquired other aggregate companies and chemical companies to expand their empire, while also growing organically. It was in 2005 when they sold their chemical division, Vulcan Chemical, to Occidental Petroleum, thus making them a pure play aggregate company. After that sale, they went back on their roll of acquiring other gravel pits and companies really until now and they show no sign of stopping. In 2021, Vulcan acquired U.S Concrete making Vulcan the most valuable aggregate franchise in the world (according to Vulcan).

Current state of things

The culmination of all those acquisitions has led to a huge company if measured by tons of reserves in the ground. Vulcan has 16.2 billion tons in reserves, which will last roughly 80 years. That's enough rock to give 277 pounds to every human that ever lived. What's even more interesting is just how difficult it is to get into this industry. As the company shows in their 2019 investor day, it has taken six decades to reach a meaningful scale and even then they only operate in 20 states, really only in the South. To even get a pit in the first place there has to be rocks to dig up, which in some places there just isn’t the correct type or there isn’t any at all. Next the local government needs to approve it and who the hell wants a rock pit next to their house, so good luck getting approval on any project remotely close to a large number of people. Then after all that your pit could still fail because of the distance from the construction. For example, rates in California are roughly $0.35 per mile and common landscaping gravel costs $40-45 per ton, so it really doesn’t take much to kill your margins. Thus distance from the pit to construction sites is extremely important and luckily for Vulcan, 50% of Americans are within 50 miles of a Vulcan pit. That's some pretty unreplicable scale, especially when considering, on average each company only operates two pits. This long tail of small companies provides outstanding opportunities for Vulcan to continue their acquisitions and expand their company.

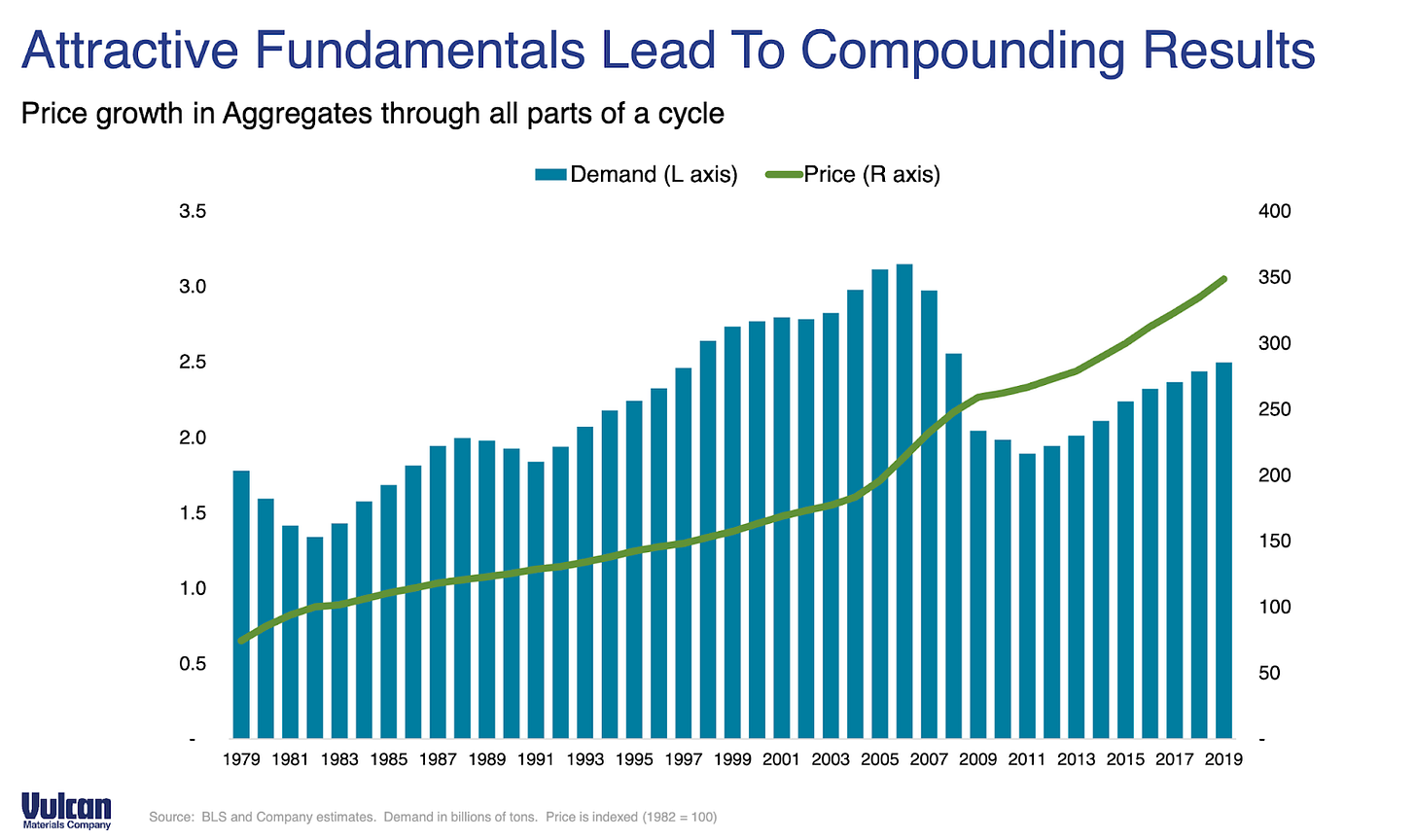

The long term demand for aggregates comes from population growth resulting in more homes being built and more jobs to be done, which is always a nice demand driver to have, since it should always go up and to the right over a long enough period of time. The short term demand for aggregates is affected by construction projects, both private (hospitals, homes, etc) and public (highways, sewer systems, etc), so an increase in home buildings or government projects drastically increases demand and making demand cyclical; however the price strangely has always continued to grow, albeit at different rates.

Even during the Great Financial Crisis, the price of aggregates grew ever so slightly as demand almost halved (the stock went down over 75% from peak to trough). This may be because there are no substitutes for high quality aggregate, an example being recycled concrete. Some projects may be able to be completed with the cheaper recycled concrete, but building specifications must be met and recycled concrete rarely meets those standards.

There is a roughly even split between public and private demand for aggregates with public accounting for 42% of total aggregate shipments in 2021. Over the long term this roughly evens out to a 50/50 split. Publicly funded projects are usually vested over years, thus providing a high degree of certainty into aggregate shipments. There’s a weird dichotomy going on with the industry being both cyclical and stable at the same time. I can’t think of too many other industries with similar qualities. Speaking of public funded projects, the recent infrastructure bill should probably be discussed. This infrastructure bill provides almost $350 billion dollars over 5 years for highway, road, and bridge construction or repair. Ultimately, what percent Vulcan will get from this is unknown, but there could be some surprising revenue growth out of them in the future, especially since city officials think making a 26 lane highway is a good idea because they don’t understand what induced demand is.

Private demand is much more cyclical and depends more on economic cycles. The higher the demand for hotels and discretionary spending means the more hotels, malls, and other buildings will get built. Pretty standard cyclicality. Interestingly, the states where Vulcan operates have had and will most likely continue to have more housing built, but ultimately interest rates are a big factor. Vulcan also sells their aggregates for a bunch of random uses like sea wall protection, ballast for railroad tracks, adhesives, and limestone can be sold as coal power plant scrubbers to reduce emissions.

The various acquisitions, especially U.S Concrete, have also resulted in some downstream integration with concrete and asphalt production as well. These business lines are complementary and often use the unsold aggregate from Vulcan’s pits and buy a chemical mixture from a third party to make the asphalt or concrete. Asphalt, like aggregates, also must be close to the construction site due to the rapid hardening of the mix. It's pretty much the same for concrete, but instead of a chemical mixture they buy cement. (I had no idea that concrete and cement were two different things until yesterday, but basically concrete is the rocks and cement is the binding agent. The random knowledge you get from investing is pretty incredible) Vulcan also has one calcium mine in Florida that mostly sells to water treatment companies, not really important, but yeah they have one.

To wrap everything up this segment quickly, Vulcan operates in a space with some incredibly high barriers to entry, but is slightly cyclical over the short to medium term. I really like this characteristic actually, the volatility in the stock price should provide some incredible buying opportunities. From the bottom of the financial crisis to its 2021 peak, Vulcan generated an above 20% irr.

Valuation

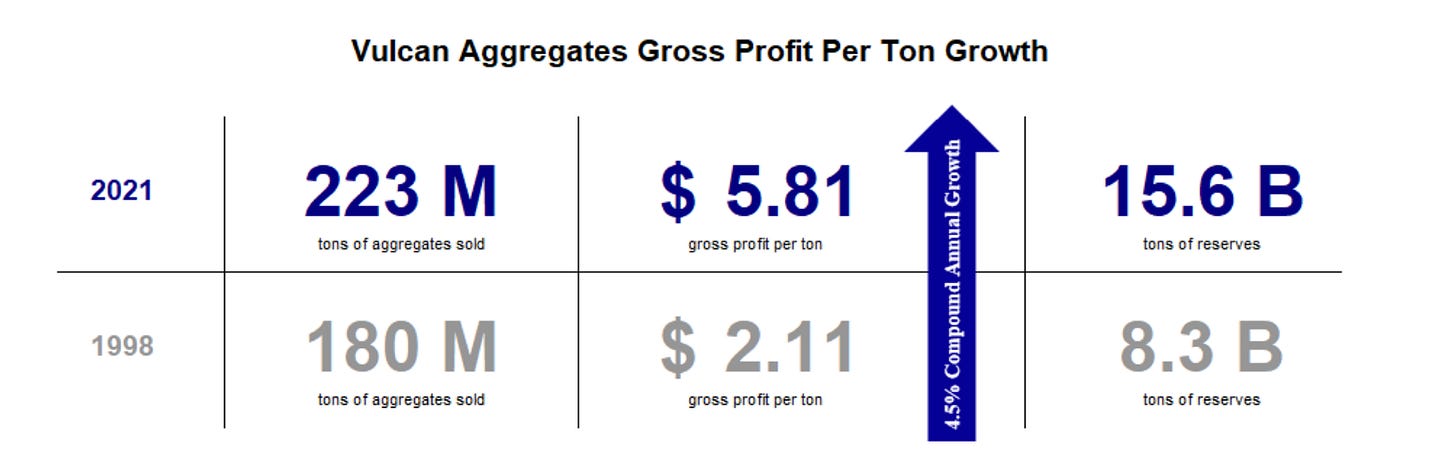

The growth formula is once again pretty simple here: profit per ton + amount of tons shipped. I know you could make it more complex, but as Albert Einstein said “Make everything as simple as possible, but not simpler.” So how have they done on a profit per ton basis?

Well that's a nice 4.5% cagr over 23 years, so it's pretty clear to see that over the long term they do have non-cyclical growth. Since 2Q’ 13 the gross profit per ton has actually grown at 12% annually largely thanks to scale. I would expect gross profit per ton to continually increase as current pits reach the end of their life cycle and Vulcan continues to acquire pits or develop their own. However, it is important to note that the start of the growth Vulcan is showing is in 2013, pretty much the year when aggregate prices started to rise dramatically. That 12% annual growth number may be slightly inflated, but I’m not so sure. Furthermore, I really don’t like betting on acquisitions for growth. The only concern for acquisitions in this industry would be management over paying and with so much experience it's unlikely, but still possible. Looking at the price growth of aggregates over the last 40 years, it averaged close to a 3.5% growth rate, so most of the growth in gross profit is coming from operating efficiency gains, which can only grow so much. The 23 year average of 4.5% makes much more sense to me than the potentially over earnings of the last few years.

The demand for aggregates over the long term is definitely positive, but hardly. The 40 year cagr is roughly 0.5%. This number is potentially deflated due to the below average number of houses being built over the past few years, along with a lack of infrastructure development. (until this year of course) From the bottom of the cycle in 1982 until 2019 the annual growth was ~1.5%. Personally, I don't see this number fluctuating too much one way or the other over decades. There will eventually be another economic boom followed by a bust, the population will always be growing, people will always be building, and the government will always be building roads that are too big. Forecasting 1% growth here seems pretty reasonable. Of course this is much lower than the 7% that has come from the last few years, but as I said earlier, I don’t like counting on future acquisitions for growth.

The long term growth, depending upon how bullish or how willing you are to bet on future acquisitions, is probably mid single digits to mid double digits (2.5% fcf yield + 5.5% growth). With no share buybacks to boost returns, the mid single digit returns + dividend yield will hardly give an outstanding return (assuming there is no huge rerating). Buying Vulcan at 30x earnings will probably result in somewhere around a 6.5% annual return. At 20x fcf and assuming it takes 5 years to rerate to 30x, it's more of a 16% irr. The organic growth really won’t generate any alpha in my opinion, of course its extremely unlikely management sits on their hands and does nothing in the future, but then again insider ownership is only 0.21%. Even assuming mid-double digit growth would require a rerating and if / when that does occur other companies will most likely also be trading at a depressed valuation, which will probably provide a better opportunity.

I really thought I was going to like this company a lot more than I do now. There's a lot of stuff to like with the incredible moat and the snippets of information in their 10k, like cash gross profits or them defining ROIC. Unfortunately, everyone now knows that the aggregate business is great, so PE firms may swoop in at appropriate multiples, causing Vulcan to pay up, and even if that doesn’t occur, Vulcan will probably never reach a sub 20x earnings valuation for me to even think about starting a position. (The one potential buying opportunity could be caused by reduced profitability because of diesel costs) Considering Vulcan is more or less tied to economic cycles, it would surprise me if Vulcan is ever trading below general market multiples, thus there probably won’t be a good buying opportunity relative to other opportunities. Will you lose money investing? If you did, I would be impressed, so it could be an investment for certain people, just not for me.

You may realize this is a bit worse than my last two write ups. Since this is basically a journal for me to look back on, companies I start to like less while going through them will have worse write ups. About half way through I started to have doubts on the potential for Vulcan to outperform the market, so I began to lose interest in doing a formal write up after I understood the business. I could totally be wrong, but there's plenty of fish in the sea. If you like the aggregate business, then maybe check out FRP holdings. I’ve just seen it on VIC a few times, never looked too hard.